Testing

5 minute read

Generalities

In the goal of asserting the quality of a software, testing becomes a powerful tool: it provides trust in a codebase. But testing, in itself, is a whole domain of IT. Some common requirements are:

- having those tests written with a programming language (most often the same one as the software, enable technical skills sharing among Software Engineers) ;

- documented (the high-level strategy should be auditable to quickly assess quality practices) ;

- reproducible (could be run in two distinct environments and produce the same results) ;

- explainable (each test case sould document its goal(s)) ;

- systematically run, or if not possible, as frequent as possible (detect regressions as soon as possible).

To fulfill such requirements, the strategy can contain many phases which each focused on a specific aspect or condition of the software under tests.

In the following, we provide the high-level testing strategy of the chall-manager Micro Service.

Software Engineers are invited to read it as such strategy is rare: we challenged the practices to push them beyond what the community does, with Romeo.

Testing strategy

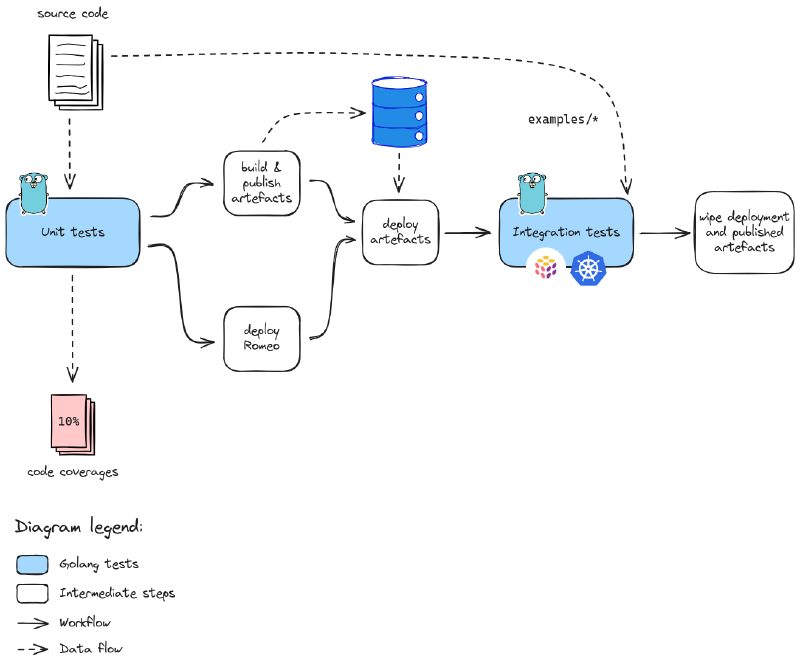

The testing strategy contains multiple phases:

- unit tests to ensure core functionalitiess behave as expected ; those does not depend on network, os, files, etc. out thus the code and only it.

- integration tests to ensure the system is behaving properly given a set of targets and in standard environments i.e. something similar to a production environment.

The chall-manager testing strategy.

Additional Quality Assurance steps could be found, like Stress Tests to assess Service Level Objectives under high-load conditions.

In the case of chall-manager, we write both the code and tests in Golang. To deploy infrastructures for tests, we use on-the-fly kind cluster, a Docker Registry v2, then Pulumi’s integration testing framework. This enables us to test Chall-Manager close to a production environment within GitHub Actions.

Unit tests

The unit tests revolve around the code and are isolated from anything else: no network, no files, no port listening, other tests, etc. This has the effect that each run and always produce the same results whatever the computer: idempotence.

As chall-manager is mostly a wrapper around the Pulumi automation API to deploy scenarios, it could not be much tested using this step. Code coverage could barely reach \(10\%\) thus confidence is not sufficient.

Convention is to prefix these tests Test_U_ hence could be run using go test ./... -run=^Test_U_ -v.

They most often have the same structure, based on Table-Driven Testing (TDT). Some diverge to fit specific needs (e.g. no regression on an issue related to a state machine).

package xxx_test

import (

"testing"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

)

func Test_U_XXX(t *testing.T) {

t.Parallel()

var tests = map[string]struct{

// ... inputs, expected outputs

}{

// ... test cases each named uniquely

// ... fuzz crashers if applicable, named "Fuzz_<id>" and a description of why it crashed

}

for testname, tt := range tests {

t.Run(testname, func(t *testing.T) {

assert := assert.New(t)

// ... the test body

// ... assert expected outputs

})

}

}

Integration tests

The integration tests revolve around the use of the system close to the production environment. In the case of chall-manager, we ensure capabilities but also that the examples can be used with the latest version, ensuring no functional regression.

Convention is to prefix these tests Test_I_ hence could be run using go test ./... -run=^Test_I_ -v.

They require a Docker image (build artifact) to be built and pushed to a registry. For Monitoring purposes, the chall-manager binary is built with the -cover flag to instrument the Go binary such that it exports its coverage data to filesystem.

As they require a Kubernetes cluster to run, you must define the environment variable SERVER with the IP or DNS base URL to reach this cluster.

Cluster should fit the requirements for deployment.

Their structure depends on what needs to be tested, and are use-case oriented: every test first describes in prose what is its particularity.

package xxx_test

import (

"os"

"path"

"testing"

"github.com/stretchr/testify/assert"

)

func Test_I_XXX(t *testing.T) {

// ... a description of what is the goal of this test: inputs, outputs, behaviors

cwd, _ := os.Getwd()

integration.ProgramTest(t, &integration.ProgramTestOptions{

Quick: true,

SkipRefresh: true,

Dir: path.Join(cwd, ".."), // target the "deploy" directory at the root of the repository

Config: map[string]string{

// ... configuration

},

ExtraRuntimeValidation: func(t *testing.T, stack integration.RuntimeValidationStackInfo) {

// If TDT, do it here

assert := assert.New(t)

// ... the test body

// ... assert expected outputs

},

})

}

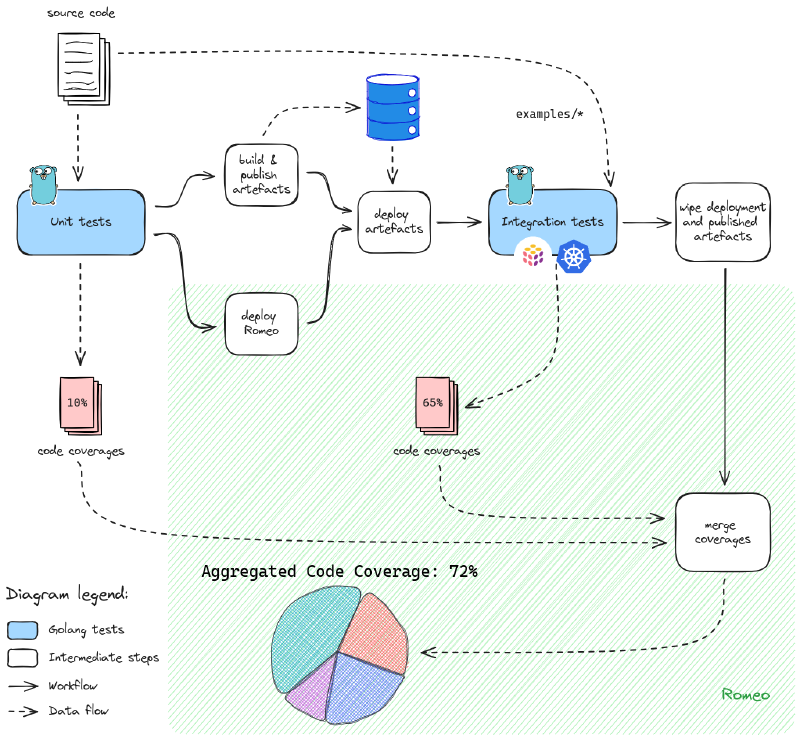

Monitoring coverages

Beyond testing for Quality Assurance, we also want to monitor what portion of the code is actually tested. This helps Software Development and Quality Assurance engineers to pilot where to focus the efforts, and in the case of chall-manager, what conditions where not covered at all during the whole process (e.g. an API method of a Service, or a common error).

By monitoring it and through public display, we challenge ourselves to improve to an acceptable level (e.g. \(\ge 85.00\%\)).

Disclaimer

Do not run after coverages: \(100\%\) code coverage imply no room for changes, and could be a burden to develop, run and maintain.

What you must cover are the major and minor functionalities, not all possible node in the Control Flow Graph. A good way to start this is by writing the tests by only looking at the models definition files (contracts, types, documentation). Then cover what seems to be important behaviors to ensure. Finally, test major issues that has been historically troubleshoot and was not covered by a test before.

When a Pull Request is opened (whether dependabot for automatic updates, a bot or an actual contributor), the tests are run thus helps us understand the internal changes. If the coverage decreases suddenly with the PR, reviewers would ask the PR author(s) to work on tests improvement. It also makes sure that the contribution won’t have breaking changes, thus no regressions on the covered code.

For security reasons, the tests that require platform deployments require a first review by a maintainer.

To monitor coverages we integrate Romeo in the testing strategy as follows.

Coverages extract performed on the high-level testing strategy used for chall-manager. Values are fictive.

By combining multiple code coverages we build an aggregated code coverage higher than what standard Go tests could do.